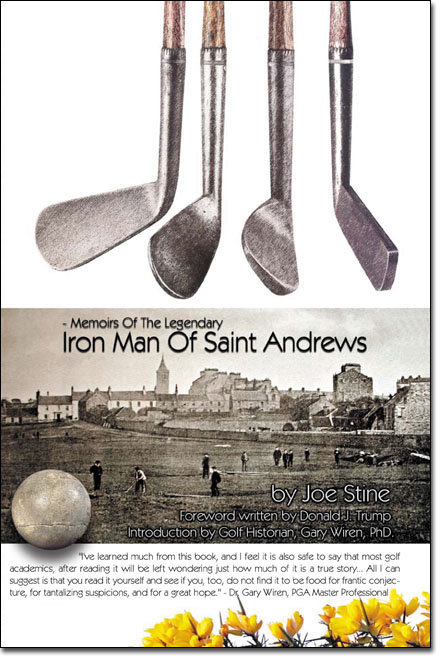

Available in Paperback, 254 Pages $17.99

Available in Paperback, 254 Pages $17.99

Photographed here: Saint Andrews as it once was, peering down North Street from the east at the Episcopal church which stood there from 1825 until 1869, when it was moved stone by stone to a new site.

Photographed here: Saint Andrews as it once was, peering down North Street from the east at the Episcopal church which stood there from 1825 until 1869, when it was moved stone by stone to a new site.

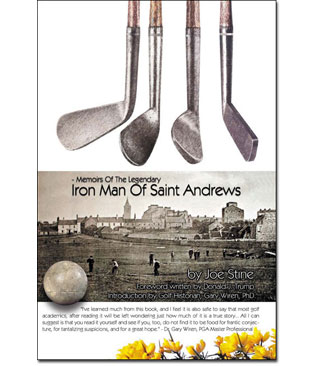

Memoirs of the Legendary

Iron Man of Saint Andrews

Iron Man of Saint Andrews

A Literary Treasure, 200 Years In The Making

Chapter 2

The Wizard O’ The North, 1827

Twas mid-June of 1827, in the wee Scotch kingdom of Fife, and the muddy streets of the ancient village of St. Andrews were busy and aflutter with news that world- renowned poet and author Sir Walter Scott was in town, visiting with the Blair Adam Club. The gossip was that Scott and his friends were said to be staying at Charleton House, the home of the Anstruthers.

Six-year-old Alec Mackenzie walked down North Street with his father, Angus Mackenzie, and grandfather, Eamonn Mackenzie. Clenched tightly under his arm, the wee lad carried a book entailing a general history of the world’s most notorious pirates.

The three Mackenzies stopped at the home of Alec’s best chum, 6-year-old Thomas Mitchell Morris, for it was Tom’s birthday and he and Alec were excited because Eamonn had promised to read to them from the wondrous pirate book that day. Upon gathering wee Tom, the four of them continued their walk through the auld grey city toward the tavern known as The Black Bull, where Angus was to meet his friend, David Robertson.

Angus and Eamonn Mackenzie were third and fourth generation golf-club and ball-makers, and that day Angus carried over his shoulder a cloth bag filled with hand-sewn leather golf balls. David Robertson had promised to meet with him at The Black Bull to introduce him to a ball merchant from Musselburgh named Gourlay.

Upon their arrival, Angus entered the establishment by himself whilst Eamonn and the two young lads patiently waited outside. Five minutes later, Angus returned with a corked gallon jug and three tin cups and handed them to Eamonn. “This may take as long as an oor (hour). When the meeting’s concluded, Ah’ll meet ye and the lads at the auld kirk ruins,” he said, referring to the old church in the old Scots vernacular ‘mither-tongue.’

Then, Angus looked down at his son and said, “Remember, Alec, ye and Tom are nae to go up St. Rule’s tower withoot yer grandfather, and most importantly, dinna tell yer mother that Ah bought this ginger beer for ye lads to celebrate Tom’s birthday or we’ll all be eat’n porridge for a fortnight.” With that said, like three happy pirates carrying their treasure chest filled with ginger beer, they set out, strolling toward the ancient ruins of St. Andrews Cathedral.

St. Rule’s tower stood next to the ruins of St. Andrews Cathedral, and its history was surrounded with a welter of conjecture. The primitive stone tower stood erect and intact in the much-churched old city, whilst around it had crumbled the cathedral, Culdee Church, the castle, priory and half-a- dozen monasteries.

There had been a religious community located on the site of the ancient auld kirk since 732 AD, when relics of Saint Andrew were brought by Bishop Acca of Hexam to what was then known as Kilrymont.

But Alec, who was home-schooled by his mother, was taught an alternative and more fanciful story; that Saint Regulus (*Riaghail, later shortened to Rule) brought St. Andrew's bones here by boat in the years after 300 A.D., having sailed from Greece and surviving a shipwreck near the site of St. Andrews’ harbor. Either way, the settlement that became St Andrews rose through the dark ages to an eminent position in the Scottish Church.

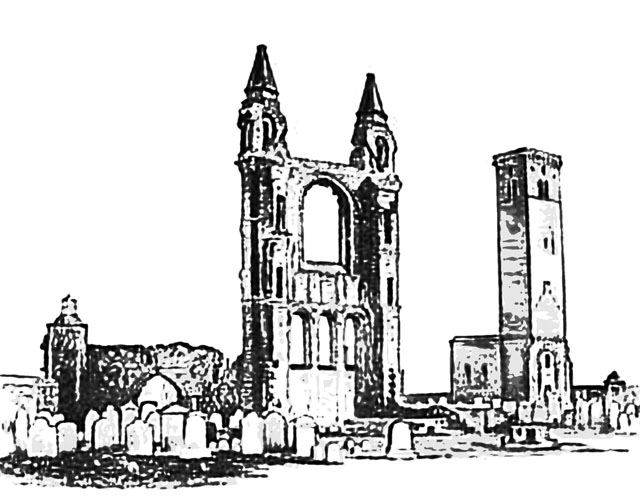

Next to St. Rule’s tower, St. Andrews Cathedral, now in ruins, was founded around 1160 A.D. and was once considered the seat of the country’s most important bishopric and largest cathedral, but there will always be conflicting stories detailing its demise.

Certainly, most St. Andreans believed the building’s destruction was the work of the riotous mob on June 14, 1559, thrown into a state of mad fanaticism by the fiery sermon of reformist John Knox. The mob of rapacious Protestant lords performed unspeakable vandalism against the treasures and culture of the medieval old church.

In pre-Reformation days, Augustinian Canons, whose rule went unchallenged for centuries, serviced the cathedral. The lofty square tower of St. Regulus, now the most prominent feature of the historical site, most likely served the dual purpose of a belfry and a watchtower. Though its height was impressive, before the sacrilegious vandalism of the Reformation, both the cathedral and the priory overshadowed the ancient chapel. Ironically, the much older tower of St. Rule survived almost in its entirety, with its once splendid neighbors now in fragments.

Saint Andrews Cathedral ruins and St. Rule’s Tower

Saint Andrews Cathedral ruins and St. Rule’s Tower

But that day, the historical significance as well as the ecclesiastical importance of the ivy-clad ruins was wasted on the trio of swashbuckling pirates. For them, the church graveyard was a magical playground where they could sword-fight with sticks and drink the forbidden ginger beer.

Upon reaching the cathedral ruins, Eamonn Mackenzie took the two wee lads up to the top of the 100-foot tall St. Rule’s tower. He then took a miniature telescope from his coat pocket and gave it to young Tom as a gift, saying, “Happy birthday, Tom!” Tom’s wee face lit up as he accepted the gift from the old man, thanking him repeatedly.

Then, careful not to leave Alec out, Eamonn pulled a second tiny telescope from his pocket and gave it to his grandson, saying, “Ye lads cinna very well be proper pirates withoot a proper spyglass.” Alec happily accepted the gift from his grandfather and also thanked him again and again. Though he did not know it at the time, Alec would keep that pocket-sized telescope for well over 80 years and think of his grandfather every time he held it.

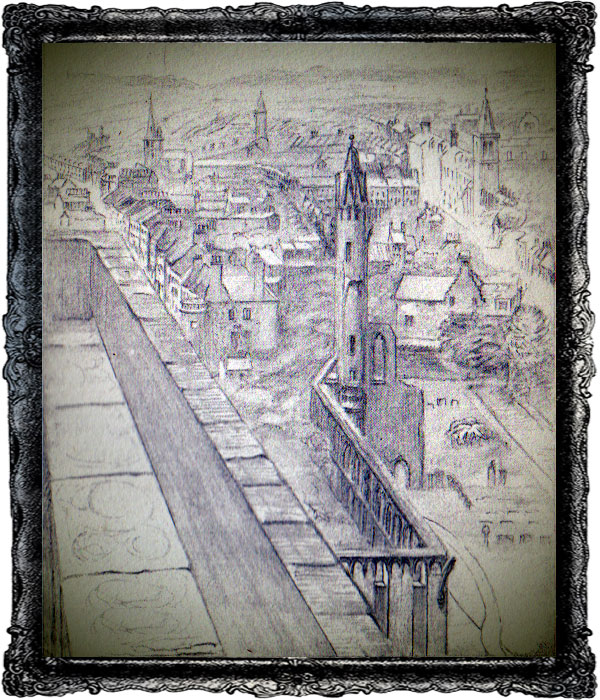

Then, from the vantage of their make-believe crow’s nest atop St. Rule’s tower, the three pretend-pirates took turns peering through the new spyglasses as they scanned their precious hometown from stem to stern.

Pictured here: The view from atop Saint Rule's Tower - 1827

Pictured here: The view from atop Saint Rule's Tower - 1827

Through the powerful little telescopes, they could see much of the old grey city, its harbor and the surrounding countryside. They could see with the greatest of detail as they looked far up both North Street and South Street. Down by the sea, they could clearly see the relics of the crumbled towers of Bishop’s Castle. The castle, though once well nigh impregnable, in the course of history had been captured and recaptured several times by the likes of William Wallace and King Edward I of England.

Though the height (108 feet) from atop the old square tower was dizzying, Eamonn and the two lads unanimously agreed that the view was indeed breathtaking and well worth the climb. When they descended the tower stairs, a group of aristocratic members of St. Andrews’ gentry, preparing to ascend the tower, met them at the bottom.

One well-dressed member of the group chose to stay at ground level as they began their ascent. Unbeknownst to the old man or the lads, it was the eminent writer Sir Walter Scott, who sat there alone on a moss-covered gravestone, busy writing in a wee notebook.

Eamonn and the two lads walked across the graveyard and sat upon a giant stone slab covering three stone coffins. It was near the site of the High Altar, where for many a century, kings, nobles and peasants, all most certainly had bowed to their knees.

Excited at the prospect of drinking ginger beer, they laid out their tin cups as 6-year-old Alec pulled the cork from the jug with his teeth. Upon seeing that, his best chum Tom exclaimed, “Save the cork for silybodkins!” Sillybodkins was a golf-like game in which the young boys would hit corks and stones with sticks up and down the sullied streets of St. Andrews using such things as doorways and lampposts as targets.

Eamonn took the jug from his grandson, saying, “Ye best let me pour, Alec,” and he filled the three tin cups to their brims, with ginger beer spilling nary a drop. Although ginger beer normally was made with fermented yeast, that day it most certainly contained only water, sugar, lemons and ginger.

The old man raised his tin cup in the air and proposed a toast, “To the golden age o’ pirates,” to which the two wee lads happily raised their cups, then drank their treasured libation. At that moment, they heard the lone man chuckling under his breath. They turned and looked at him as he stared down at his notebook, trying not to eavesdrop.

Alec then handed Eamonn the book that he had so diligently carried and said, “Now, grandfather, will you please finish reading the story about what happened to Blackbeard the pirate?” The old man answered, “Verra well, lads, but ye must swear nae to tell yer mother. For Ah knaw that ye’re aware that she forbade the reading o’ this heathenness book to ye.” “We promise, grandfather,” answered Alec. “We swear, sir,” echoed wee Tom.

The old book itself was a bit of a literary oddity. Though Alec and Tom considered it to be quite riveting, it was indeed poorly written in the fact that it had many lengthy sentences that would ramble on for all of an entire paragraph. But, they were pretend-pirates, not literary critics, and they loved the old book and thought it to be wonderful.

Smiling, Eamonn began by saying, “Verra well then, we last left off at the part o’ the story whaur Captain Edward Teach, itherwise knawn as Blackbeard, and his sparse crew o’ only 14 blood-thirsty pirates had jist boarded o’er the bow o’ poor Lieutenant Maynard’s sloop.”

Then he read aloud, quoting verbatim every word of the poorly written old book.

“Blackbeard and the lieutenant fired the first pistol at each other, by which the pirate received a wound, and then engaged with swords until the lieutenant’s unluckily broke. As Maynard was stepping back to cock a pistol, Blackbeard was at that instance striking with his cutlass, but one of Maynard’s men gave Blackbeard a terrible wound in the neck and throat, by which the lieutenant came off with a small cut over the fingers.”

“Ah bet that made Blackbeard mad,” shouted Alec. “Shut yer yap,” snapped Tom. “Ah want to hear whit happened next.” Surprised by wee Tom’s outburst, Eamonn paused and looked up for a moment. He smiled as he pushed his spectacles up, refocused and then continued to read aloud from the wondrous book.

“They were now closely and warmly engaged, the lieutenant and 12 men against Blackbeard and 14, ’til the sea was tinctured with blood round the vessel. Blackbeard received a shot into his body from the pistol that Lieutenant Maynard discharged, yet he stood his ground and fought with great fury, ’til he received five-and-twenty wounds, five of them by shot. At length, as he was cocking another pistol, having fired several before, he fell down dead by which time eight more out of the 14 dropped; and all the rest, much wounded, jumped overboard and called out for quarters, which was granted, though it was only prolonging their lives for a few days. The sloop Ranger came up and attacked the men that remained on Blackbeard’s sloop with equal bravery ’til they likewise cried for quarters. “Here was an end of that courageous brute, who might have passed in the world for a hero had he been employed in a good cause.”

Looking a bit stunned, Alec asked, “That wasn’t truly the end of Blackbeard, was it?” “Ah’d nae worry aboot ol’ Blackbeard,” quipped Tom. “He cinna be killed.” At that moment, the lone Scott, still sitting beneath St. Rule’s Tower, shouted over to them, “What happened to Blackbeard’s body?” Looking a bit puzzled, Eamonn answered, “Ah’m nae sure.” Scanning the text for a moment, he turned forward a page of the book and continued to read, “It says here, the lieutenant caused Blackbeard’s head to be severed from his body and hung up at the bowsprit end.”

“Ewww,” exclaimed Alec, “I cinna believe they did that to him.” “Aye,” laughed Eamonn, “perhaps ye lads may wish to rethink want’n to be pirates,” Looking a bit squeamish, the two lads stared at each other for a moment and then started to laugh. Reinvigorated by the sugar in their ginger beer, they both suddenly jumped up and started running around, playing and larking about the ancient graveyard.

At that point, the lone Scott, groaning as if wrought with pain, slowly stood, and then started walking toward Eamonn. His limping left no doubt that he was troubled by his right leg. As he approached the old man, he politely inquired, “Please pardon my curiosity, sir, but was that book published in 1724?” Surprised by his inquiry, the old man turned to the front of the book and searched for a date. Then he answered, “Aye, twas indeed, sir. How is it that ye knew that?”

As he hobbled over and sat down on the stone slab next to Eamonn, he answered, “It seems, my good man, that we share a common fondness for great works of literature. I have that book in my library. It’s entitled ‘A General History of the Robberies & Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates,’ by one Captain Charles Johnson.” Reaching out to shake Eamonn’s hand, he introduced himself, “My name is Walter Scott, sir.”

As they shook hands, Eamonn replied to his newly made friend, “Ah’m pleased to meet ye, Walter. Ah’m Eamonn Mackenzie.” Pointing toward the two lads, who were busy play-fighting with sticks, he added, “And o’er there, engaged in swordplay, is ma six-year-old grandson, Alec, and his wee best chum, Tom.” Giving a wink, he added, “They’re blood-thirsty pirates, ye knaw!” Smiling, and in complete agreement, Sir Walter remarked, “Of course they are. That’s evident by the level of skill at which they’re displaying for us their swordsmanship.”

As the lads continued to lark about, Eamonn, being the consummate gentleman, asked, “Cin we welcome ye wi a drink, Walter?” “Welcome is the best dish in the kitchen,” replied Scott. With that, Eamonn refilled one of the tin cups with ginger beer for his new friend.

After thanking him, Scott took a drink from the cup and said, “This ginger beer would make a fine whisky-toddy.” “Indeed it would” Eamonn chuckled as he reached into his jacket and pulled out a flask of whisky. He then added a wee bit of the “water of life” to both cups, and said, “To ye and yer health, Walter.” After both men raised their cups and took a drink, Scott said, “I believe that to be the best toddy I’ve ever drank.” “Aye, and the mair ye drink, the better it gets,” replied Eamonn.

With that the two elderly men cemented their friendship and began chatting away as if they’d known each other for years. “Tell me, Walter, why did ye nae choose to view the old grey town from atop St. Rule’s tower,” asked Eamonn? “Tis a lovely view, y’knaw.”

“I decided not to go up the tower as I’ve done on former occasions,” answered Sir Walter. “This is a bit of a falling off on my part, I must confess, for normally I would never remain sitting below when there was a steeple to be ascended. Auld sparrows are indeed ill to tame, you know. But rheumatism has begun to change my way of thinking, for today I seemed content to merely sit on a gravestone, whilst recollecting the first visit I made to St. Andrews, 34 years ago.” With a sigh, he added, “What many untold changes in my feelings and fortunes have since then taken place!”

Intentionally changing the subject, the world-renowned author then said to the elderly ball maker, “So Eamonn, have you read many of my books?” To which the old man replied, “Oh! So ye write books, do ye Walter?” Looking a wee bit disappointed, Sir Walter answered, “Well, nothing really important.” Then, he asked, “How about Robert Burns? Surely you’ve read the work of the Ploughman Poet?” “Aye, Rabbie Burns,” answered Eamonn. Then, with great pride, Eamonn quoted what little Burns he knew by heart, reciting, “Wee sleekit, cow'rin, tim'rous beastie, O, what a panic's in thy breastie!” Hearing the old man’s rendition of Burns’ poem, “Address to a Mouse,” Sir Walter smiled from ear to ear, saying, “That’s very good, my friend. I suspected that you were a man of considerable culture.” “Aye,” said Eamonn, “the Bard o’ Ayrshire is ma verra favorite minstrel.”

Poor Eamonn, who was not much of a reader, was totally unaware that his new friend, Sir Walter Scott, was the single most prominent figure in English literature at that time. Nor had he noticed that Walter’s bust or picture was in virtually every shop window in St. Andrews, not to mention the rest of Scotland.

Then, Scott inquired, “Do you read the Bible much, Eamonn?” “Aye, tis the only book Ah read,” retorted the old man. He laid his tin cup down, then squinting a wee bit, he looked at Scott directly in the eyes and said, “Why do ye ask, are ye a spiritual man, Walter?”

Sir Walter thought for but a brief moment, then answered, “Well, Eamonn, that would depend on what you meant by spiritual. Now, my father was a zealous Presbyterian and was always very formal and precise in the manner of my upbringing. One might even say that he was excessively strict in such matters as the observance of the Sabbath. And then there was my dear, saintly mother. She, I would say, was most assuredly religious.”

“That’s lovely, Walter,” snapped Eamonn, “but are ye spiritual?” With one eye noticeably twitching, the old man stared Scott in the face and clarified his inquiry, “Do ye knaw aboot spirits?” “Only what I’ve read,” replied Scott. “Why do you ask? Do you believe in ghosts, Eamonn?”

The old man found himself taken back by Scott’s powers of deduction. Wary, he leaned back and answered, “Ah’ might. Do ye?” Scott grinned with interest and then calmly asked, “Have you ever seen a spirit, Eamonn?” Hesitating a bit, he answered, “Ah’ might’ve. Have ye?”

Politely, Sir Walter answered, “I’ve yet to witness the manifestation of a spirit, but if you have, I would most appreciate hearing about your experience.” Scott sensed the poor old man’s reluctance to speak and gently prodded, “Eamonn, my good friend, when was the last time you saw a spirit?”

The old man thought, but still hesitated from answering the question. Scott studied him but for a moment, then rephrased his enquiry, “Do you see spirits in this graveyard now, Eamonn?” “Nae spirits,” answered the old man, “jist ane spirit.”

Very calmly Scott lowered his voice and asked the old ball-maker, “Eamonn, who do you see in spirit?” The old man answered, “Tis m’dear auld departed father.” Sir Walter then asked the old man, “What does the spirit of your father want?” “Ah believe he jist wants to watch oot for me, cause he loves me and feels Ah’ll always be his wee bairne laddie (*little baby boy).” Sensing that more was said, Scott then asked, “Does your father say anything else?” “Nae,” answered Eamonn.

Careful of his new friend’s sensitive state of mind, Scott smiled and said, “That must be most reassuring for you to know, Eamonn. You are a very fortunate man. I would hope that my dear departed father is watching over me.” Then, after a long moment of deafening silence, Sir Walter added, “When I was a lad, still studying at the University of Edinburgh, I once read that Leonardo Da Vinci said, ‘As a well-spent day brings happy sleep, so a life well spent brings happy death.’”

Trying his best to understand of what his friend spoke, Eamonn asked, “Leonardo who?” “Da Vinci,” answered Scott. “He was an Italian artist during the early 16th century, but that’s not important. The point is that death is deaf and will hear no denial.” Then, staring down into his tin cup, he went on to say, “With this in mind, I must confess that hearing you speak of your deceased father with such warm regard somehow lessens my own fear of the inevitable.”

Seemingly reassured that Walter was not poking fun at his expense, Eamonn grinned, then picked up the jug and again partially filled two of the tin cups with ginger beer, after which he topped them off with whisky from his flask, and said, “Ah propose a toast, Walter.” As the two gentlemen both picked up their cups, Eamonn said, “To the spirits o’ our fathers,” to which Sir Walter added, “may they live forever in our hearts.”

Sensing it safe to confide in Walter, the old man looked at him and said, “Ah hiv to confess, Walter, ma father’s spirit did say one mair thing.” Curious, Scott looked at Eamonn and in a very calm voice asked, “What else did your father say, Eamonn?”

The old man hesitated and then replied, “Ah’m nae sure o’ the mean’n, but his words were, ‘Walter haes a verra auld spirit.’ ” Hearing this perplexed Sir Walter. Scratching his head, he pondered for a few moments, then smiled and calmly said, “A very old spirit, how odd.”

Alec, who was standing close by, had heard his grandfather’s conversation with Sir Walter and thought it odd indeed. He wondered if his grandfather was speaking figuratively about a religious experience, or did he really believe in ghosts. That particular aspect of his grandfather’s personality would remain a mystery to Alec for another 28 years.

A minute later, the group of Sir Walter’s gentry friends came down from atop St. Rule’s tower. They went straight toward him and all began talking at once whilst simultaneously biding for his attention. At that moment, Alec let out a blood-curdling scream as wee Tom hit his finger with a stick during their pretend sword fight. Alec ran crying to his grandfather, as Scott’s entourage began to surround Sir Walter in a riotous manner.

Amongst the chaos and bedlam, Sir Walter fought his way back through the mob of aristocrats and managed to reach his hand out to the old man and said, “I would gladly trade all the books in St. Andrews to spend the rest of my day with you three swashbuckling pirates instead of gentry, my friend. Social status means nothing in choosing one’s friends.”

Quoting Robert Burns, Sir Walter then said, “The rank is but a guinea stamp, ’tis a man’s character that is the true gold.” Shaking hands with Eamonn, he then spoke in the mother tongue, “Guid fowks are scarce, Eamonn. Take care o’ yerself.” Sir Walter then looked down at the tears in the 6-year-old’s eyes and added, “And you, Alec Mackenzie, remember ne’er to let sorrow sit near your heart,” adding, “I think it was the great philosopher Blackbeard the pirate that once said, “Be happy while you’re living, for you’re a long time dead.”

Hence, having said his goodbyes, Sir Walter turned around and left the graveyard of the auld kirk of St. Andrews, accompanied by his riotous entourage of St. Andrean aristocrats. As they meandered further down the muddy street, the church ruins grew quiet.

The graveyard seemed very still after the crowd had left. Soon Alec’s father, Angus, returned from The Black Bull with good news for everyone’s ears. He had sold all his feather golf balls for cash and received a large order for more balls from the Musselburgh ball merchant he had just met.

It was not until that evening at the dinner table that Alec’s father and mother heard about Eamonn and the lads meeting their new friend, Walter. As she was serving dinner to the family, Alec’s mother, Rosmairi, said that her employer, who was one of the regents (*professors) at the University of St. Andrews, had the especially great honor of meeting the world-renown author and poet Sir Walter Scott in person that day. It was to this end that she attested, “Whosoever would have imagined Sir Walter being of such graciousness and kind spirit. He was sweet tempered to the point of being merry, generous to a fault and well beloved, yet peremptory and pertinacious in pursuit of his own ideas.”

Without looking up from his plate, Eamonn said to his daughter-in-law, “That disna sound like Walter Scott to me.” To which Rosmairi said to the old man, “What would you know of the ‘Wizard o’ the North?’ You’ve never even read one of his books.” “Well, lassie, since ye asked, though he dinna say anything aboot being a wizard, today Walter Scott told us that he wad gladly trade all the books in St. Andrews to spend the rest o’ his day wi Alec, Tom and myself.”

Chastising the poor old man, Rosmairi said, “Shame on you, Eamonn Mackenzie, teaching your grandson to lie like a drunken sailor! How dare you tell such a story right in front of him! Lord only knows what other wretched business you’ve filled his head with today!”

Just then Alec spoke up, “No, mother, it’s true! We spent the afternoon with Walter Scott today at the auld church ruins.” Just itching to wash his mouth out with soap, Rosmairi scurried into the next room, brought back an opened book from the parlor, showed it to Alec, and asked him to identify the man pictured. Unbeknownst to Alex, it was a picture of another famous author, Lord Byron.

Alec took one look at the page and said to his mother, “I don’t know who that man is, mother. Is this a game, because that is not Walter Scott?” Rosmairi turned red as she got angrier by the minute and grabbed the book from the child. Thumbing through the pages, she then handed it back to Alec and said “How about this man?”

Alec took one look at the picture and said, “That’s him. That is grandfather’s best chum, Walter Scott.” Rosmairi’s jaw dropped as Eamonn then said, “Let me see that book!” Upon scrutinizing the page, he concurred, “Aye! That’s ma good mate, Walter. Tisna a verra fair likeness o’ him though. They got the plaid vest right, but this picture makes him look fat. He isna fat at all. He’s a wee bit better look’n than that, wouldna ye say, Alec?”

Eamonn and Alec then told the lad’s mother and father all about their meeting Sir Walter Scott. Of course, they omitted any mention of the pirate book or ginger beer or whisky, but that still left plenty to tell. From that day on, Rosmairi told everyone that her son was a close personal friend of the “Wizard of the North.”

Alec would long remember Eamonn’s conversation with Sir Walter, but it would be another 28 years before he would truly understand his grandfather’s words about the afterlife.

The End Of Chapter 2

Table of Contents - 31 Chapters, 254 Pages

- Prologue – (Auction of the Circa 1800 ‘Ringmaker’ Iron)

- The Memoirs - The Wizard O’ The North, 1827

- Rosmairi Mackenzie & The Land O' Leal

- Learn’n Golf - The Game O’ Life (Old Course 1831)

- The Robertsons (Peter, Davie & Allan)

- Hugh Philp (The Stradivari of Clubmakers)

- Ball Mak’n (“Balls are whaur the money is.”)

- The Art O’ Club Mak’n

- The Apprentice, 1834 Blacksmith’n, “a vocation wi’ a future”

- Putter & Haggis, 1846

- Captain Mac 1846, Niver beat the landlord at golf

- The Ol’ Union Parlor, Tales of Chinese pirates & opium wars

- Rosmairi’s Gaelic Home, 1847 (Coontie O’ Ayrshire)

- Two Hole Course, Uncle Murdoch’s intro to golf

- Muireall McEwan’s 100th Birthday

- Turn’n O’ The Caber, (Anja)

- If It Isna Scotch, Tis Nae Whusky!

- Eat’n O’ The Haggis (haggis eat’n weary-whiddle)

- ‘The Day Efter’

- Master Cleekmaker

- Wi’ Birth Comes Death, 1848 (Winnie's Birth)

- Saint Andrews, 1852

- The Iron Man Visits Prestwick, 1854

- Death O’ Angus Mackenzie

- Test’n Cleeks Wi' Tom Morris

- The New Clubhouse at Saint Andrews, 1854

- A Wager Made

- The Golf Match (the Old Course in 1854)

- Home Hole

- The Golden Years

- Epilogue

Available at Amazon.com

This historical novel presents a revealing look into the real history of 1800s Saint Andrews Scotland and its golfers. Based on real events, the 93,000-word memoirs entail a hauntingly in-depth account of the Iron Man's 89 well-spent years of life and golf within the enchanted royal burgh of his birth, beginning mid-June of 1827, when at age six, he and his six year-old best chum, wee Tom Morris met "The Wizard of the North," Sir Walter Scott beneath St. Rules Tower in the graveyard amongst the ruins of St. Andrews Cathedral.

Available on Kindle $12.99 at Amazon.com

Available on Kindle $12.99 at Amazon.com